SUBMISSIONS

ARTWORK

RESEARCH TEXTS

WORD WOES 2 (MAP)

Dedicated to Karel Schoeman (1939-2017)

2018

Size of wall: 13630 mm X 4450 mm X 375 mm

Edition of wall: 4

1/4 at MAP (Modern Art Projects) Richmond, Northern Cape Province

2/4 is to be adapted and built as a free-standing wall at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, England in 2019

2 X artist proof walls were erected in the development of text and wall

Proof No. 1 at SMAC Gallery, Woodstock, Cape Town (2015)

Proof No. 2 at Liedjiesbos, Bloemfontein (2016)

WORD WOES (MAP) was created at the MAP (Modern Art Projects) Artists’ Residency and Gallery in Richmond, Northern Cape Province

62 Loop Street, Richmond, Northern Cape 7090

Director: Harrie Siertsema

Associate: Morné Ramsay

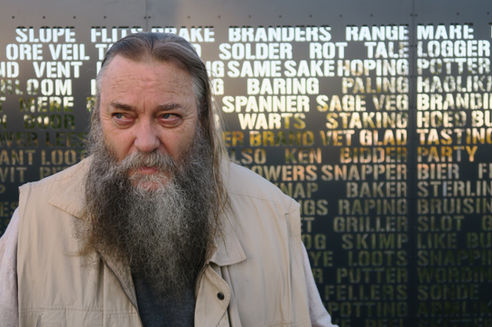

The work WORD WOES (MAP) is a wall-structure created along a side wall of the expansive MAP Art Gallery. It is constructed of locally produced clay bricks each bearing a letter of the alphabet. These spell out singular words in curious Afrikaans/English linguistic relationships.

South Africa boasts eleven official languages. The largest South African language group is isiZulu, spoken by 22.7% of the population. The second largest language group, isiXhosa, is spoken by 16.0% of the population. Afrikaans (13.5%) and English (9.6%) rank third and fourth.

Afrikaans is spoken by almost all the the people of the Northern Cape Province where the WORD WOES (MAP) wall is located.

It should be noted that under English/British rule in the early twentieth century, the Afrikaans language was outlawed at school and in public service. In WORD WOES each English word might be seen as hiding a secret Afrikaans word that it had once failed to exterminate.

The bilingual title WORD WOES, in English, implies a state of distress and sorrow caused by words, but in Afrikaans these same words instruct us to behave in a behave in a frenzied and wild manner.

The total of of 390 words ‘spelled out’ by the letter-bricks include both English and Afrikaans words of the same spelling, but having different meanings. To the English reader with no knowledge of Afrikaans the words will appear to be English only and their Afrikaans meanings will be lost. To Afrikaans readers the Afrikaans meanings will be clear and so might the English meanings since all Afrikaans speakers have a fair understanding of English.

The block-pattern formed by the overall grid is inspired by the pattern of a sheet of graph paper. These grating lines are enhanced by deep fluting between bricks. Some of my early artworks were motivated by my enjoyment of crossword puzzles. There is an oblique reference to these works in the vertical and horizontal arrangement of the brick letters of WORD WOES.

The manufacture of the bricks was undertaken by a local Richmond brick company called Werk Trek of Vrek, inherited and run by Mr. Trevor Snijders in collaboration with MAP. The WORD WOES project has managed to generate employment to several artisans and brickmakers of the impoverished town of Richmond.

-

Each alphabet brick has a single letter, cast in intaglio relief. Two blank bricks are used as filler between words.

-

The lines of words fray irregularly to the left and right of the wall where they are rounded off by blank bricks.

-

The type-face for upper-case block letters was designed by Mr Trevor Snijders. A unique and rather ad hoc type-face was generated due to Mr Snijder’s limited knowledge of typography.

-

The forging and baking of the bricks in a large brick kiln under extreme warm weather conditions in the harsh open veld of this semi-desert Karoo landscape has given the bricks a rough and rustic appearance.

-

The wall was treated after construction with 3 coats of stone sealer.

-

It was constructed by a team of bricklayers, using scaffolds, profiles, wheelbarrows and brick force ties.

-

The new wall of letter bricks is anchored into MAP Gallery’s pre-existing back-wall.

-

Measurement of a single alphabet brick 115 mm X 115 mm X 75 (measurements varying slightly)

-

Measurement of a single stock brick 115 mm 205 X X 75 mm (measurements varying slightly)

Total number of bricks on the facade as in the MAP, Richmond wall:

Number of bricks – letter A 155

Number of bricks – letter B 65

Number of bricks – letter C 0

Number of bricks – letter D 73

Number of bricks – letter E 318

Number of bricks – letter F 16

Number of bricks – letter G 112

Number of bricks – letter H 29

Number of bricks – letter I 125

Number of bricks – letter J 2

Number of bricks – letter K 69

Number of bricks – letter L 136

Number of bricks – letter M 52

Number of bricks – letter N 136

Number of bricks – letter O 149

Number of bricks – letter P 99

Number of bricks – letter Q 0

Number of bricks – letter R 198

Number of bricks – letter S 174

Number of bricks – letter T 150

Number of bricks – letter U 25

Number of bricks – letter V 16

Number of bricks – letter W 42

Number of bricks – letter X 0

Number of bricks – letter Y 6

Number of bricks – letter Z 0

Number of blanks – face 1593

Total number of 115 mm X 115 mm X 75 mm blank bricks for both edges, left and right, of the wall: 272

Related works include:

THE WRITING THAT FELL OFF THE WALL (1997)

See: https://www.willemboshoff.com/product-page/writing-that-fell-off-the-wall

WAILING WALL (2017 previously referred to as JERUSALEM JERUSALEM)

See: https://deskgram.net/p/1791664109549541702_415458515

WRITING IN THE SAND (2000)

See: https://www.willemboshoff.com/product-page/writing-in-the-sand

NEGOTIATING THE ENGLISH LABYRINTH

See: https://www.willemboshoff.com/product-page/negotiating-the-english-labyrinth

Origins of the WORD WOES project

A direct relation may be drawn between the Word Woes work and an earlier work titled PLATTER ROOSTER TASTING

In May, 2011, I visited Stellenbosch to discuss the town’s envisaged Twenty exhibition with SMAC Gallery. Painfully aware of the squabble over Afrikaans as a language of prerogative at Stellenbosch University at the time, I proposed an artwork consisting of one word that makes some sense in both English and Afrikaans, but of which the meanings in the two languages differ significantly. That work was to be titled BOOM. I envisaged it to be a big gabion wall (a bulky wall of stones stacked into a structure of wire baskets) Stones in two different shades would be stacked inside the wire baskets to spell the word ‘boom’ on both sides of the wall. The wall would be located in Jonkershoek, a get-away nature reserve where romantic couples often enjoy sanctuary in the shadows of large trees beneath spellbinding vistas of mountain cliffs. My gabion wall had to be wide, high and inviting enough to serve as a refuge for amorous kisses.

The word ‘boom’, in English, is rather onomatopoeic and spells out the noise of exploding bombs, as in the big boom! In the Russian navy, boom! is an accepted toast, like cheers! In a more sedate sense, boom is also a long pole, usually pivoted to go up and down to let traffic through. In Afrikaans boom is ‘tree’ a word that appeals to my life-long interest in and respect for flora. I have tried to learn the names of all the plants I have come across and I am doing quite well in this venture. Boom, however, has another, far more stress-free meaning in Afrikaans. To the unperturbed it indicates marijuana (Cannabis sativa). The more easygoing students would immediately chuckle at this usage and might be tempted to slink behind the BOOM wall for a whiff or two of the beleaguered stuff. I wanted the work to poke some light-hearted fun at the obsessive linguistic preoccupation of the frantic local academic fraternity. It would clearly satisfy them on one level and most certainly raise eyebrows on another. Unfortunately I never made the artwork BOOM, but there is every reason to believe that I might make it one day.

The idea that one can have words of the same spelling in Afrikaans and English, which differ totally in meaning, stayed with me. When I was approached by SMAC gallery in Stellenbosch, to have a solo exhibition in 2012, the memory of BOOM milled about in my head and I began to collect similar words. During the year before the exhibition I managed to come up with two-hundred-and-forty words.

To stay with the idea of using the earthen substance (stones) envisaged for BOOM, I decided to use the sands and soils from the town of Darling, also in the Western Cape. I mapped out the words on small wooden plaques and arranged the plaques in a collage comprising a muted checkers design resembling a wall of 240 bricks. Each ‘brick’ contained a word and to form a perfect formatting, I allowed myself only six letters per plaque. To my disbelief I discovered three seven-letter words that did not fit into the design. They are platter rooster and tasting. These three words obviously had to feature somewhere and they turned into the title of the artwork.

WORD WOES (etching)

At the completion of PLATTER ROOSTER TASTING I was convinced that I would not find any new words, but in the two years that followed new words began to surface and when I was put to bed for months on end by an awful flu at the beginning of 2014, I had time to contemplate new additions. In the end the 240 words increased to 290 and in order to share the work with a wider audience, I decided to turn it into an edition of etchings with the new title WORD WOES. In English, this title laments issues related to words and in Afrikaans it instructs us to let go and be wild.

The idea of a brick wall was retained in the design of the WORD WOES etching, each block still containing one word.

Word Woes (Wall)

The PLATTER ROOSTER collage and the WORD WOES etching were well received, but they merely resembled brick walls. In 2015, I built an actual wall out of real bricks. The bricks were carefully planned in collaboration with brickmakers from the small town of Richmond where fluent Karoo Afrikaans is the mother language and where everyone thinks that to speak even a broken kind of English, is rather grand.

I spent months consulting my English and Afrikaans dictionaries constantly discovering new words and the first WORD WOES wall was built in 2015 at SMAC Gallery in Woodstock, Cape Town. A second WORD WOES wall was built in 2016 in the garden of the Liedjiesbos (bush of little songs) estate in Bloemfontein. The number of words increased from the etching’s 290 to 390. To honour the Afrikaans and English-speaking people of Richmond the wall was then built in their town, in 2018, still using their own brickmakers with their own type face design. The wall now had 451 words

What started of as ‘fun with words’ ended up as an idiosyncratic monument to language. Don’t forget, just as much as the English words on the wall are a truly serendipitous Dada mix, so too are the Afrikaans words on the wall happy Dada flukes. There is actually such a monument to Afrikaans – the taalmonument in Paarl, Western Cape. Paarl is the neighbouring town to Stellenbosch where my exercise in the marriage of unlikely English and Afrikaans articulations began. An internet search for a monument to the English language did not deliver any results, so my wall might veritably also be the only monument to English in the world. As it turns out, Afrikaans is the only language in the world that has erected its own monument.

It would be ironic if the only monument to English were erected in England, in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park on the back of a language it had once tried to eliminate. Such a monument, it must be said, would also be a conceptual, avant-garde artwork, challenging existing concrete poetical expressions in all languages. The WORD WOES project is not intended to belittle any language over another. It began in a free-spirited way with PLATTER ROOSTER and it is still committed to build tolerant bridges between Afrikaans and English by appealing to a sense of humour.

The survival of Afrikaans under British colonial rule is due to the fact that it had developed in challenging circumstances for a few hundred years before English arrived. The English attempt at the linguistic cleanup of ‘dirty’ languages resulted in an unprecedented resolve to maintain and preserve Afrikaans that often bordered on the fanatical. Afrikaans is the language of choice of thousands of authors, all of them very well versed in English. A growing list of Afrikaans authors worthy of the Nobel prize is available. The irony is that they might only be awarded such as a result of their works being translated into and published in English.

The South African author J. M. Coetzee (born 1940-) received a whole host of awards, most notably the Nobel Prize for Literature (2003). All his writing is in English, but he is from Afrikaans heritage and he is fluent in Afrikaans. He is of the opinion the the South African ‘condition’ can be better expressed in Afrikaans than in English, stating that the English turn of phrase becomes somewhat strained in dealing with the land, and its people. In White Writing 1988, he says that one cannot write the South African landscape in English as eloquently as in Afrikaans.

There is no logical linguistic reason for the choice of words in WORD WOES. In a way they are a Dada list – a mini Dada dictionary. Their inclusion is strangely dependent on the throw of a dice, in this case, the dice is the fact that the English and Afrikaans meanings of these words of the same spelling have absolutely nothing to do with each other. In Dada poetry, for example, chance plays a definitive role. A book might, for example, be opened blind and at random. The very first piece of text one might put one’s finger on is then used. This is repeated until some rather quaint and refreshing selection of texts is obtained. This method of unfathoming ‘truth’ is also called logomancy. The selection offered by the WORD WOES text is is the fluke result of truly conceptual happenstance.

The marvel of it all is for the reasonably bilingual person to read a word from one of the two languages, and then, upon reflection, to find the meaning of that word in the other language slowly dawning upon them.

At first, I considered calling the work LOST IN TRANSLATION because the words play with irreconcilable meanings. This ‘English-only’ title would, however, only serve to anger sensitive members of the Afrikaans community and I decided to name the project after two of the words that strangely make sense when combined: WORD WOES.

The English often see Afrikaans words next to English signage and because of their expectation that all written expression everywhere must necessarily be English, one often gets quite humorous readings. My son, Willem junior, who lives in the United Kingdom, once tried to draw money from the automatic banking machine in the predominantly Afrikaans town of Parys and he could not because he thought the prominence of the word jammer on the monitor meant that the machine had been jammed, when in fact an apology was issued for the fact that the machine could not print paper slips. Jammer in Afrikaans means ‘sorry’. An old English friend wondered for a while about the meaning of the word slegs on a road sign – he read ‘only slegs’ and could not, for the life of him, figure out what kind of things the slegs are. In Afrikaans slegs means ‘only’.

WORD WOES (Yorkshire Sculpture Park 2019)

The wall envisaged for the Yorkshire Sculpture Park will be a free-standing wall. Its façade will duplicate the Richmond (MAP) wall, but the same text will be repeated on the back of the wall. This back and front repetition is an ironic stab at the obsession with bilingualism that existed in South Africa for most of the twentieth century. Every official document had to be issued twice, all signposting reflected two languages. The freestanding wall conforms to this duplication. The front/back repetition of text was also used in WAILING WALL (2017), a free-standing art wall built at NIROX Sculpture Park, west of Johannesburg.

All bricks on both sides (front and back) and both edges (left and right) of the wall as envisaged for the free-standing wall at Yorkshire Sculpture Park: (All of these are double the amounts given for the wall existing at MAP Gallery, Richmond)

Total number of bricks on the facade:

Number of bricks – letter A 310

Number of bricks – letter B 130

Number of bricks – letter C 0

Number of bricks – letter D 146

Number of bricks – letter E 636

Number of bricks – letter F 32

Number of bricks – letter G 224

Number of bricks – letter H 58

Number of bricks – letter I 250

Number of bricks – letter J 4

Number of bricks – letter K 138

Number of bricks – letter L 272

Number of bricks – letter M 104

Number of bricks – letter N 272

Number of bricks – letter O 298

Number of bricks – letter P 198

Number of bricks – letter Q 0

Number of bricks – letter R 396

Number of bricks – letter S 348

Number of bricks – letter T 300

Number of bricks – letter U 50

Number of bricks – letter V 32

Number of bricks – letter W 84

Number of bricks – letter X 0

Number of bricks – letter Y 12

Number of bricks – letter Z 0

Number of blanks – face 3186

Total number of 115 mm X 115 mm X 75 mm blank bricks for both edges, left and right, of the wall: 544

WORD WOES DICTIONARY DEFINITIONS.

Casual rules for the selection of words

WORD WOES is an eccentric dictionary made up of words of the same spelling in English and Afrikaans but with totally different meanings. The meanings contained in its expressions are meant to be straight-forward, easily understandable, aimed at astonishment and admiration for their linguistic flair. I hope to ambush a certain slice of our former bilingual society with the work’s quaintness and I mean to keep them at a standstill for some time in front of the work, pondering the marvelousness of our differences. Preference is given to words that are more or less easily identifiable and that might cause the greater interest.

My friends playfully came up with two small sentences that read true for both languages: “My hand is in warm water” or “My pen is in my hand.” Unfortunately all these words are totally synonymous for Afrikaans and English and none such totally similar words are admitted in WORD WOES. Entries were omitted if they did not succeed as excellent examples of a true kind of difference.

Words that might normally be accepted in the game of Scrabble are suitable, but note the following relaxed rules:

Tested words Reasons for excluding words from WORD WOES

Exact synonyms in Afrikaans

and English not allowed

Near synonyms in Afrikaans

and English not allowed

elf

mars

spit

mark

ken (removed in WW 3)

spring

toner

toning

dwang

vader

swat

toon

laggies

suffer

hook

bedel

arsering

tome

nog

brag

rust

ween

lam

slams

prat

reef

roes

frees

big

weens

bros

mag

bots

gat

reël/reel

reëls/reels

blase/blasé

waterbase

roofing

winding

winning

rooms

EXCEPTIONS TO THE RULES

vet

veg

stat

teen

intel

latte

vroom

waterfees

waterfee

badwater

roomwater

Words that are synonymous in English and Afrikaans are not allowed. The project is based on words spelled exactly the same, but that carry no similarities of meaning.

hang, arm, hand, was, spit, drank, hinder, note, verse, rose, grief, pan, vat, ring, stand, stank, sending, slinger, sing, plot, filter, water, warm, tirade, stink, hand, later, letter, blind, film, sit, spring, item, arm, inkpot, etc.

When the degree of synonymity in English and Afrikaans is too great, words are disallowed.

pure, blank, grade, rose, note, innerlike, manlike, prater, skipper, plotter, flap, span, state, slurp, bale, bedding, bolster, mild, slip, waker, plate, etc.

Words with more than one meaning, of which one of the meanings is the same in English and Afrikaans are also disqualified.

‘Eleven’ in Afrikaans is OK, but as Santa’s little helper (same meaning in English and Afrikaans) it is disqualified.

Mars, ‘to spoil’ in English and ‘to march’ in Afrikaans, is acceptable, but ‘Mars’ as the planet Mars in both languages falls out.

Spit is ‘to eject saliva’ in English and in Afrikaans it is to turn soil over, but a roasting on a skewer is the same in both languages

Mark as ‘tick’ or ‘to denominate’ is OK in English, but the synonymity as market in both languages disqualifies it.

Ken is ‘chin’ in Afrikaans, but in both languages it denotes one’s range of knowledge or insight.

Both languages have spring as a sense of ‘jump’ but in English it is also a natural source of water.

Strained meaning - avoid

In Afrikaans, ‘one who shows’ - it is conceivable that the word can be used, but it is not in the Afrikaans dictionary.

In Afrikaans, ‘act of showing’ - it is conceivable that the word can be used, but it is not in the Afrikaans dictionary.

Avoid informal, colloquial or seldom used words.

OK - dwang ‘coercion’ in Afrikaans. Not OK - ‘serious trouble’ (he is in the dwang) in colloquial English.

OK - ‘father’ in Afrikaans and an abbreviation. Not OK - ‘Dark Vader’, a character from the Star Wars films.

OK - ‘to hit or slap’ in English. Not OK ‘to study’ in informal Afrikaans.

OK - ‘toe’ in Afrikaans. Not OK - short for ‘cartoon’ film in informal English.

OK - bits of laughter in Afrikaans. Not OK - US slang for laid back, leisurely slickers who are always late and ‘lag’ behind.

OK - In English, ‘to hurt from bad, unpleasant things’; Not OK - ‘more mentally worn out’, from suf, is strained Afrikaans.

OK in English. As an exclamating Hook! ‘stop! (from hokaai!) not OK in Afrikaans

In some English universities, an official with ceremonial duties. OK in Afrikaans - to beg for handouts, privileges or money

Children sensitive

In Afrikaans, hatching applied to drawing; shading-in in line drawings; English: free-spirited adults only

No foreign or archaic, obscure, pedantic, scientific or overly technical words.

‘Reins of a horse’ in Afrikaans; ‘book’ in old English.

In English, ‘small block or peg of wood’ (seldom used) and short for ‘eggnog’; In Afrikaans it means ‘more’ or ‘still’.

‘To boast’ in English; ‘to have brought’ in archaic Afrikaans.

‘Oxidation’ in English; ‘to rest’ in archaic Afrikaans

‘To be of opinion’ in archaic English; ‘to cry’ in Afrikaans

‘To hit’, a verb in nineteenth century English; ‘lamb’ in Afrikaans.

In English, ‘shuts with force’, ‘smashes’; in Afrikaans – of the Cape Coloured Muslim people (derogatory)

In English, ‘incompetent or stupid person’, idiot, ‘buttocks’; ‘proud’ in Afrikaans is archaic

In English, ‘ridge of rock, coral, or sand’, ‘vein of ore’; ‘hand sail’ is too obscure in Afrikaans

In English, as plural for ‘roe’ deer, it is too obscure; acceptable as ‘rust’ in Afrikaans

In English, to release from confinement or slavery, ‘to let go’; ‘to mill or trim’ metal is too obscure in Afrikaans

OK in English. Big as ‘piglet’ or ‘young pig’ in Afrikaans is too obscure

In Afrikaans ‘because of’ but the English ‘to be of the opinion’ or ‘to think or suppose’ is too archaic

No abbreviations unless they are used so often that they have become common language

Disqualified as abbreviation for ‘brothers’ in English; but acceptable as ‘brittle’ in Afrikaans

Acceptable as ‘power’ in Afrikaans; unacceptable as abbreviation for ‘magazine’ in English

Acceptable as ‘to crash’ in Afrikaans; unacceptable as the abbreviation for ‘robots’ in English.

English abbreviation for ‘gatling’ gun not acceptable. Afrikaans for ‘hole’

Words with diacritical marks, capital letters or spelling discrepancies are not allowed

‘To stagger’ or ‘film spool’ in English is acceptable; as ‘rule’ or ‘precept’ in Afrikaans, it is not allowed

‘To stagger’ or ‘film spools’ in English is acceptable; as ‘rules’ or ‘precepts’ in Afrikaans, it is not allowed

‘Blisters’ in Afrikaans; but blasé in English has an acute accent mark and is not accepted.

In Afrikaans, authorities dealing with water issues; In English it should be two words: water base ‘consisting mainly of water’.

In English, ‘material and process for constructing a roof; In Afrikaans ‘scabbing’ or ‘robbing’ - the spelling is strained, obscure.

In English, ‘twisting movement or course’; as ‘windy’ the spelling is strained and obscure in Afrikaans.

In English, ‘to be victorious’; as ‘making progress or headway’ the spelling is strained and obscure in Afrikaans.

Acceptable in English, but the capitalised Afrikaans Rooms is rejected (pertaining to the Roman Catholic Church).

Exceptions to abbreviations are allowed if they are more generally used than their proper terms

English abbreviation for ‘veterinarian’; ‘obese’ in Afrikaans.

English abbreviation for ‘vegetables’; ‘to fight’ in Afrikaans.

In English, short for photostat or statistic; ‘primitive town’ situated in rural area in Afrikaans

In English, a teenager or pertaining to teenagers (informal); Afrikaans for ‘in opposition to’; ‘hostile to’; ‘adjacent to’ or ‘touching’

English abbreviation for military or political information – now an accepted word. Afrikaans for ‘picking up and loading in’.

In English, ‘coffee made espresso steamed in hot milk’ – not spelled as lattè. Afrikaans for long, straight stems or wooden slats

OK - as ‘prude’ or ‘God-fearing’ in Afrikaans; OK - as onomatopoeic English for a certain machine sound, often used

Singular words

Mostly two words in English, but instances of fusion into singular words exist. OK in Afrikaans

Mostly two words in English, but instances of fusion into singular words exist. OK in Afrikaans

Mostly two words in English, but instances of fusion into singular words exist. OK in Afrikaans

Mostly two words in English, but instances of fusion into singular words exist. OK in Afrikaans